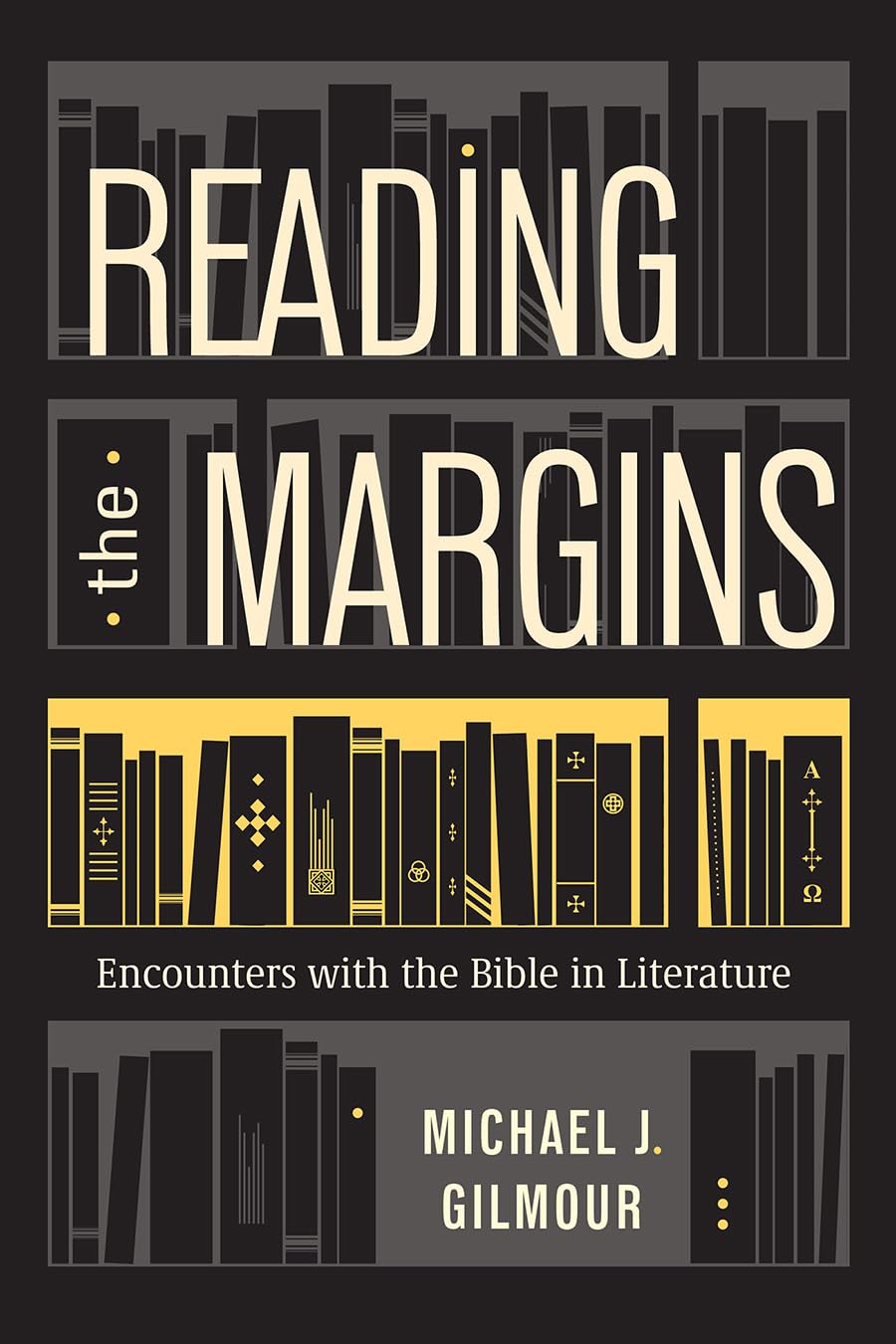

On Wednesday, October 9th in the courtyard at Providence, a couple dozen staff, faculty and students gathered for the launch of Dr. Michael Gilmour’s new book Reading the Margins: Encounters with the Bible in Literature. Dr. Gilmour is Distinguished Professor of New Testament and English Literature at Providence University College, where he has worked as part of the faculty since 1998. He is the author of a number of books, including Creative Compassion, Literature and Animal Welfare (2020), Animals in the Writings of C. S. Lewis (2017), Eden’s Other Residents (2014), and The Gospel According to Bob Dylan (2011). In this latest release from September 24th of this year, Dr. Gilmour examines what literature and the Bible as conversation partners can teach readers about ethics. Below is a recent conversation that Providence had with Michael Gilmour (MG) about Reading the Margins.

What motivated you to write Reading the Margins?

MG: I’ve always been interested in the intersection of the Bible and creative writing. The reception of the Bible and the arts generally has been a long interest. So, I thought this would be a good opportunity to choose some of my favorite authors, look at the ways that they engage with Christian themes or biblical content, and bring them all into one place. I’m drawn to the idea that exploring the arts helps us better understand some of the themes that we find in biblical texts. I was playing a bit with the idea of fiction providing a lens through which to read the Bible and better understand some aspects of it – especially ethical issues. That was the motivation behind it.

Who is the intended audience of the book?

MG: I assume that anybody reading anything with the subtitle, “Encounters with the Bible in Literature,” would be interested in both the Bible and fiction, and looking for connections between them. You never quite know who’s going to pick up a book, but I’d like to think it’s somebody sitting in the pew, who takes the Bible seriously, and who is drawn to story and narrative as a way of interpreting the world around them.

As an author, what is it that compels you to write?

MG: For me, it’s the best part of my job. I find it relaxing and it also gives me an excuse to read the books I want to read. Maybe the most practical thing though is that it serves the classroom. I find almost everything in this book has shown up somewhere in class. In particular, there’s a course called “Religious Themes and Literature,” which I’ve taught for 20 years now. There, I play with ideas, take them to the students and walk through things with them. Sometimes it lands, sometimes it doesn’t. But all of it becomes grist for the mill that I hope brings a kind of freshness to students. I always feel that the best classes tend to be the ones where I’m not quite sure the answer to what it is I’m talking about. That’s the moment in teaching I really love, and I try to connect this to the writing I’m doing.

In what way does literature “open up” the biblical text?

MG: The Bible tells us to care for the poor. Not all of us have the same understanding of what real poverty looks like. But reading the stories of others can sometimes awaken something in us – a better understanding of what it means to care for those who are in need or vulnerable. If we assume the Bible wants us to care for all categories of the helpless, it seems to me that this could be a useful way to get a handle on what vulnerability looks like. My loose guide for the book was the story of the Sheep and the Goats from Matthew 25: “I was hungry, and you fed me; thirsty and you gave me something to drink; in prison…” and so on. We don’t always know what those really look like. However, by reading widely, perhaps we get a better handle on what the Bible is actually calling us to do.

How do approaches to reading literature help us to understand the Bible better?

MG: Bringing the lens of literary criticism to the biblical texts is useful – not only relating to how authors develop plot and use characters in narratives like the Old Testament, the Gospels, and the book of Acts, but also with respect to ethics. For instance, feminist and post-colonial approaches often bring to the surface the overlooked, the marginalized, and the vulnerable. So, when you’re reading a text through this lens, you may notice those who are not given names, or which characters are overlooked or not given a voice. Those kinds of subtleties can point us in the direction of a whole group of people that might be disregarded in a narrative by an author.

Is there a difference when reading either literature or a sacred text?

MG: Certainly, we put the Bible in a different category as foundational; it’s an authoritative text. But to say that the Church, Scripture, the Christian tradition and the Creeds are at the heart of everything doesn’t mean that there isn’t also truth outside. Sometimes the scriptures ask us to do things that on the surface we can’t do on a certain level, like “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” I can pray for those who persecute me, but the process of loving my enemies is something that has to be trained. I see literature that helps me understand my enemy better as contributing to the sacred narratives. They’re teachers, nudging me in the direction of compassion.

How does reading Scripture and literature together foster empathy?

MG: It seems to me that when the Bible calls us to love one another, it’s more than a loose sympathy, but actually entering into the grief or suffering of another person. You weep with those who weep. But if I don’t know that other person, the depth connection is more difficult. So, if I read the stories of those who suffer in those ways, maybe it’ll help close that empathetic gap that exists. I play with the idea of reading literature as a sort of spiritual discipline – going into a book and asking, “What can I learn from this text?” and being open to the possibility that Christ might be in these unexpected places. When I read a novel by Charles, Dickens, I like to imagine that if I’m attentive to its calls to care for the poor, it’s serving the scriptures in the sense of pushing me in the direction of greater empathy. Not all books do this of course; but many do, and I think we benefit greatly when we’re attentive to the potential of other texts to serve the sacred.

What’s one takeaway that you hope readers will remember from Reading the Margins?

MG: That there’s much to learn in our bookshelves, and I hope someone puts this thing down, and runs to grab a novel by Salman Rushdie or somebody like that. We can read fiction not just as escapism, but we can also read books to nurture our spiritual life; to feed the soul, to aid us in our walk with God. In this way, reading a novel can allow us to see the needs around us, and make us more empathetic to those we are potentially positioned to help.

Find your own copy of Reading the Margins: Encounters with the Bible in Literature through…

…or wherever fine books are sold.